|

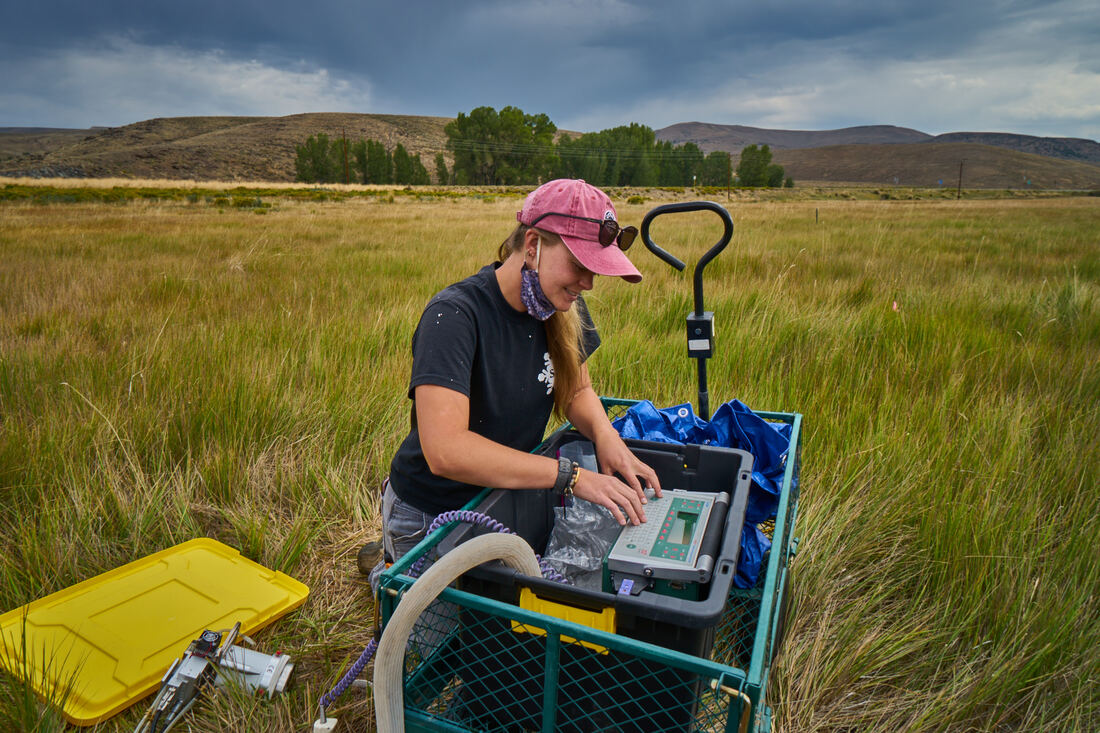

For my thesis research, I am interested in the carbon sequestration potential of rangeland soils. Rangelands present a valuable opportunity to sequester carbon as they are continually managed grasslands with high productivity. At Coldharbour, and two other rangeland sites, compost was added to the soils for the purpose of increasing soil water holding capacity, plant productivity, and carbon sequestration. These compost additions were carried out in June of 2019 by Alexia Cooper, a Western MEM Alumni. My role in this project investigates the impact that compost additions have on soil respiration, that is, the release of CO2 by microbial organisms within the soil microclimate. Using the amount of respiration given off by these microbial organisms, and by testing the amount of soil organic carbon present, I will be able to calculate the mean residence time of carbon within the soil. The major goal of soil carbon sequestration is to increase the length of time that carbon resides within the soil profile. If I am able to find that compost additions indeed increase this residence time of carbon, then implementing compost additions may be an impactful strategy employed by ranchers to improve rangeland soil health while also supporting climate change mitigation. Pictured is a piece of equipment that measures the amount and rate of CO2 released from the soil. I am also collecting soil moisture and soil temperature weekly and will be identifying the soil microbial communities within each plot in the summer and winter seasons to further understand the shifts that occur on an annual basis. I hope with the collaboration of Coldharbour Institute and Western Colorado University that my research results may go on to support impactful management strategies in rangeland soil health for the benefit of Gunnison ranchers, community members and overall environmental health. Written by Alexandra VanTill, Student in the Master of Science in Ecology and Conservation program at Western Colorado University

0 Comments

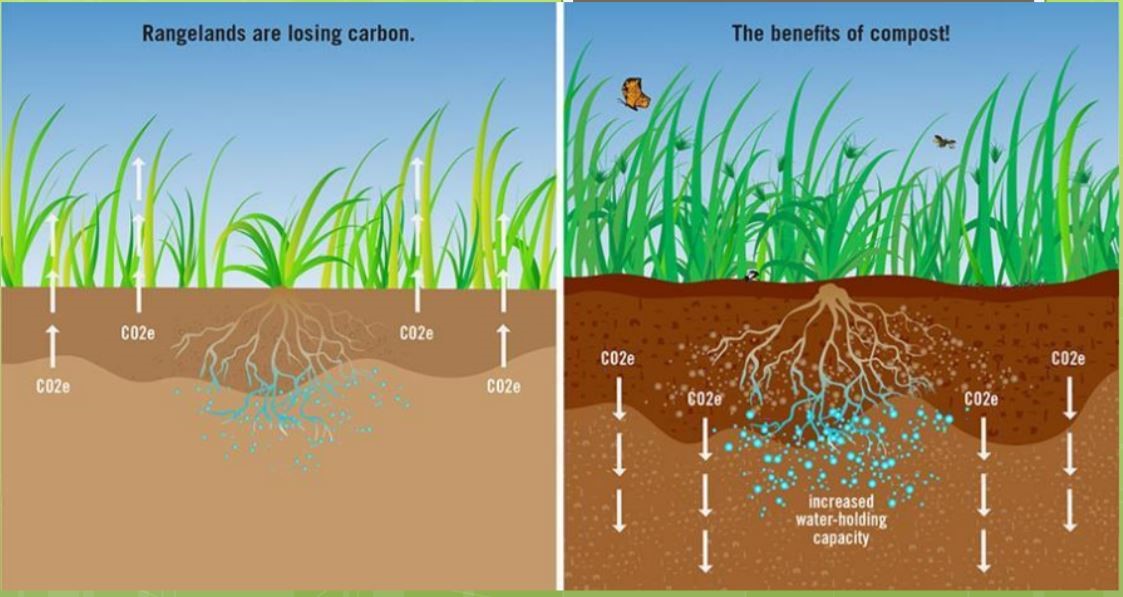

Coldharbour Institute aims to provide meaningful research that is site specific and focused on addressing the expressed needs of our community. We want the research that is developed by our team to be applicable to our region with results that drive innovation and adaption. Ranchers and academia have a fraught history that has hindered efforts for collaboration. We wish to change that, evolve it to create the change that is needed to address the issues that face our community. At Coldharbour Institute, we intentionally approach ranchers in our community with a humbleness that promotes collaboration and a co-production in knowledge to move forward issues. In the Gunnison Valley our land managers face a variety of issues from invasive weeds, wildlife conflicts, and a changing climate e.g. a longer drought period. We want to build an adaptive and dynamic relationship between Western Colorado University and that of the producers in our valley. Coldharbour Institute provides the land for us to test our research ideas informed from our community needs assessments. For many of the fellow’s projects, access to land was vital to test our land management approaches. The Coldharbour Ranch boasts a diversity of ecosystems to experiment upon, from riparian to sagebrush steppe. There is a symbiotic relationship formed by our passionate graduate students and their community-based work which provides Coldharbour with innovative research that supports our goal to demonstrate holistic land management practices to prompt adoption by our community. A drone shot taken early June by Alexia Cooper, shows the flooded Tomichi Creek and its tributaries. An Example of this Approach: Rangeland Resilience through Soil Health In Gunnison, we have a long and rich ranching history that goes back more than a century. The continuation of this ranching culture relies upon the conservation and regeneration of the perennial rangelands that ranchers rely upon. In 2018, our valley experienced a prolonged drought period, and in response, ranchers had to shut off their flood irrigation two week early to conserve water. Here in our cold high elevation climate, we have a very short growing season of just 62 frost free days. Due to the shortness of our growing season, a two week decrease in water drastically affected the yields of ranchers lands. After the economic results were felt by ranchers, they were apt to find a solution to make themselves and their lands more resilient to the effect of drought. One way to do this was to improve the health of their soil, specifically the water holding capacity of their soil. A promising approaching to achieve this was to amend their soils with compost. As a graduate student at Western Colorado University, I had just listened to a lecture by a premier soil scientist in California, Rebecca Ryals, who had conducted a research project to find out how to regenerate rangelands from the soil up. Her approach was to apply a half an inch of food waste compost to rangelands. In their first year, they saw a doubling forage production, an increase in the water holding capacity of the soil, and a 70% increase in net ecosystem storage of carbon. Her project demonstrated that it was possible to improve the health of the ecosystem; while mitigating climate change by fostering increased soil carbon sequestration. I was deeply impressed on how this project interwove community needs, climate action, and impactful policy into a monumental force for change. This inspired me to focus my master's project on a replicate study here in Gunnison. For my project I applied two inches of Class A biosolid compost to four ranches. One of the four sites was located on Coldharbour Ranch. Coldharbour Institute is my community sponsor, and they guided my research objectives to meet the needs of my community. The goals of my project was to discover if the application of compost would demonstrate similar positive effects like seen in the Californian study: improved water holding capacity, increased forage production, and increased storage of carbon from the atmosphere. Throughout the summer I monitored soil moisture, plant biomass, species diversity, soil temperature, and in the fall, I collected soils to run soil health analyses. Although it is still early in my data analysis, I observed an increase in grass production and an increase in soil moisture throughout the summer in my treatment plots. My project creates a connection between Western Colorado University and the ranching community in Gunnison, setting it up for future collaboration and growth. This revamped connection was made possible through the network and high community standing that Coldharbour Institute has built since its inception. Ranching culture promotes individualism and self-reliance and historically, ranching communities dislike academic involvement within their land management. This is due to the typical relationship that is formed: researchers go into the ranching community with a sense of superiority that often belittles and dismisses the traditional knowledge ranchers have gained through trial and error. There is little to no room for collaboration when defining the purpose and research goals of the project. Researchers conduct their projects and leave without debriefing the community about the results of their research. This is an issue that is perpetuated by a lack of good science communication. For researchers, it takes an additional awareness and intention to begin the discussion early with ranchers and managers, this prompts collaboration. And then, the researchers should conclude it by sharing how their findings can inform, for example, land management, city planning, or conservation practices. Written by Alexia Cooper, Clark FellowAfter graduating from the MEM program this coming May, Alexia will be pursuing her PhD at UC Merced working with Rebecca Ryals, from the Marin County Carbon Project, on soil carbon sequestration project in California.

|

Ongoing ResearchNotes from the field of Coldharbour Ranch. Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|

Sign up for our newsletter below.

|

|

Coldharbour Institute is a 501(c)3 Non-Profit Organization

P.O. Box 463 Gunnison CO 81230 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed