|

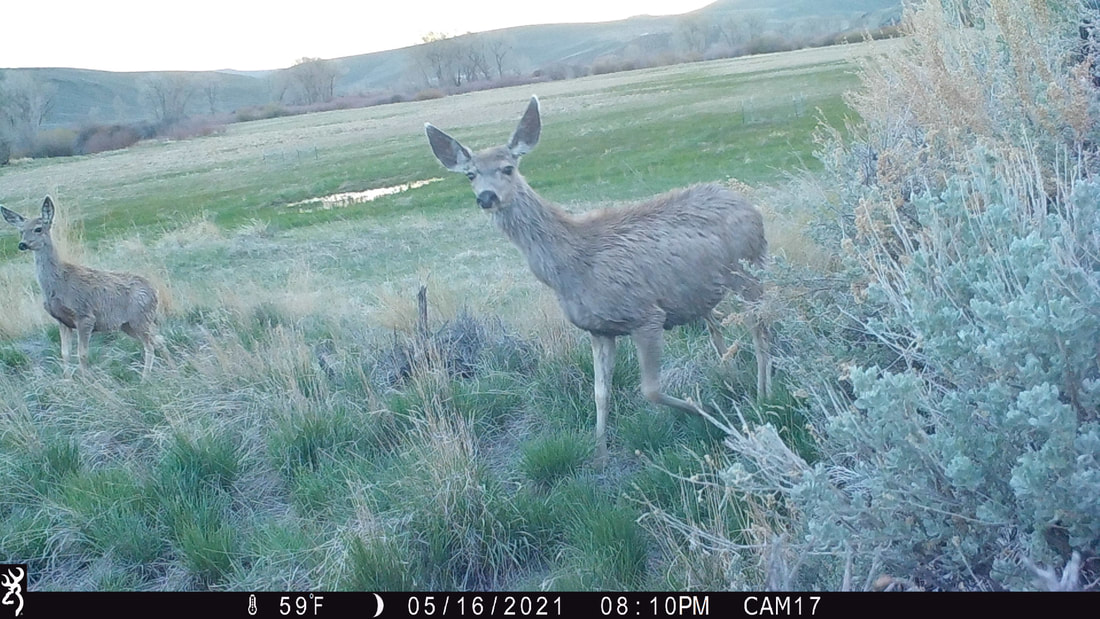

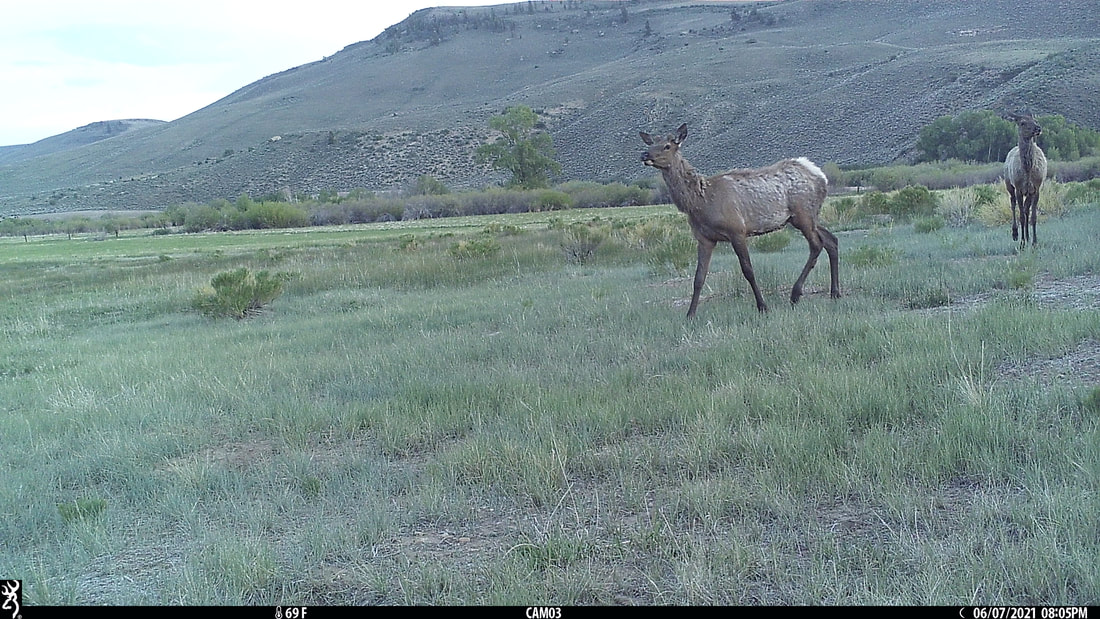

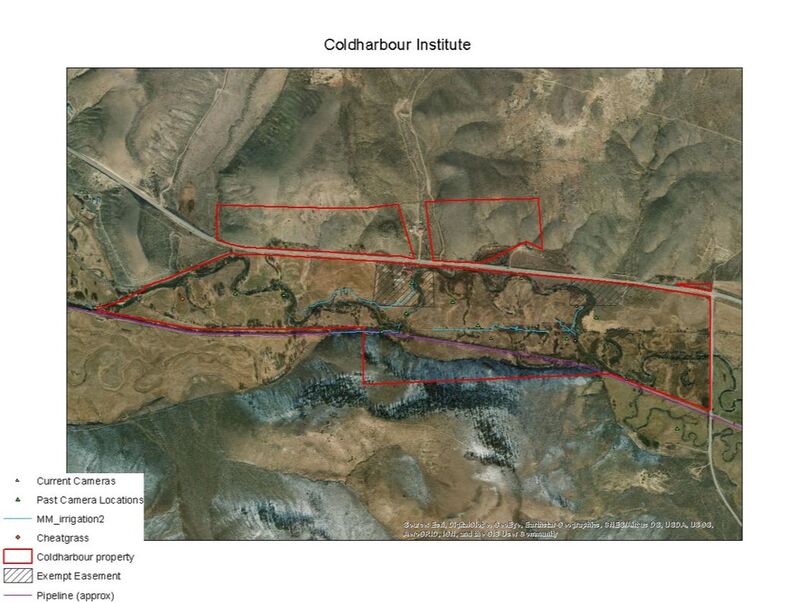

The wildlife monitoring on Coldharbour is under way! 24 cameras have been put up along the fence line of the property that borders Highway 50. This is part of Anna Markey’s masters project as part of the Masters of Environmental Management Program at Western Colorado University. She has collected the trail camera photos and tagged the wildlife seen in them since the beginning of May. The biggest interest is in ungulates detected such as mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and elk (Cervus canadensis) in order to determine where they are most likely to cross Highway 50. So far, deer and elk have been detected in abundace but there have been some other fun suprises seen on the trail cameras. Striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), coyotes (Canis latrans), desert cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus audubonii), a beaver (Castor canadensis), a badger (Taxidea taxus), and even a black bear (Ursus americanus) have been captured on camera on the property!

Most of the ungulates have been captured on camera at the East end of the property. It will be interesting to see if this is where most of the ungulates are detected especially during the fall/winter migration and the spring/summer migration. The highest species richness has also been seen closer to the East end of the property especially an area with a drainage culvert. The bear, a beaver, striped skunks, ducks (Anas spp.), mice (Peromyscus spp.), and even a house cat (Felis catus) have been captured using the culvert! This is good news because it indicates that this wildlife is avoiding crossing the higheay and a proper underpass would be well utilized by many species on the property. With the data gathered from this project, valuable information will be provided for future infrastructure on the property and across Highway 50 such as a wildlife overpass or underpass. Blog Post and Research by Research Coordinator Fellow Anna Markey

1 Comment

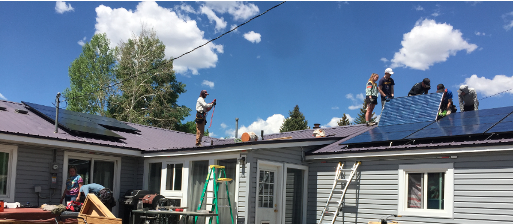

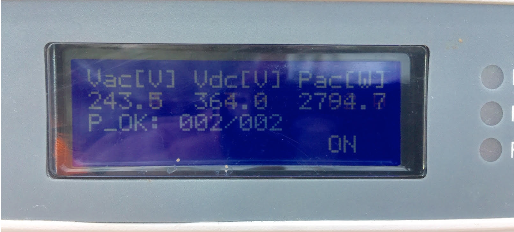

Project Report: 3.75kW Solar Array LMI Installation at 104 Floresta Street, Gunnison, CO 812308/5/2021 In 2020, the Equitable Solar Solutions program at Coldharbour Institute in Gunnison, CO approached the Colorado Energy Office to partner on a pilot project to install a reuse solar photovoltaic (PV) system on a low- to moderate-income home. After receiving a list of seven homes in Gunnison County that had participated in the Weatherization Assistance Program, ESS evaluated each home for site suitability with respect to placement of a solar PV array. Several homes were impacted by terrain and tree shading. One home visited had already installed a solar array. One homeowner is highly interested but needed to address roof repairs that have now been resolved.[1] One elderly homeowner was not interested in participating. Taylor Miller’s home at 104 Floresta St was selected due to the good southern exposure and an electrical load that is compatible with one of the PV systems in our inventory. The ESS program provided 15 PhonoSolar 250-watt (one is a 260-watt version) modules, a SolarEdge SE3800A grid-inverter, 15 SolarEdge DC optimizers[2], and Snap-N-Rack rails for the project. Our local solar installer Nunatak Alternative Energy Solutions provided the remaining hardware needed for the Snap-N-Rack mounting system, cabling, connectors, conduit, electrical boxes, meter can and labor for design, installation and commissioning. The solar PV array and inverter installation was completed on 4-Jun-2021. Duft Electrical provided equipment, wiring, components and labor to complete the system tie in with the house on 29-Jun-2021. This did require installation of an additional breaker panel on the building exterior between the production meter and the interior main breaker panel. System commissioning was completed on the afternoon of 29-Jun with the PV array producing up to 2.794 kilowatts of power mid-afternoon under partly cloudy conditions. All 15 DC optimizers and modules successfully paired with the inverter. ESS will follow up with homeowner Taylor Miller on a monthly basis for the first few months to ensure proper system operation. The total project was completed below budget at a total of $6,907.71 which includes $6,006.71 payment to Nunatak Alternative Energy Services and Duft Electrical, plus 15% administrative/indirect costs of $901 incurred by Coldharbour Institute. This results in an installed cost of $1.84 per watt – well below industry standards for non-LMI system owners. [1] Funding for a project on 102 Diamond Ln in Gunnison would be greatly welcomed by the homeowner. [2] Which also meet NEC rapid disconnect requirements. October is Energy Efficiency Month! GV-HEAT, Gunnison Valley’s energy efficiency program, wants to help you save money. Through GV-HEAT we connect households to resources that help them improve the energy efficiency, comfort, and affordability of housing in the Gunnison and Hinsdale Counties. These resources are available based on household income and can be used by both renters and homeowners. But first, we would like to extend our huge Thank You to the Coldharbour Institute for the opportunity to be highlighted as a partner. We appreciate this so much! You may be able to receive support to implement home improvements through these resources:

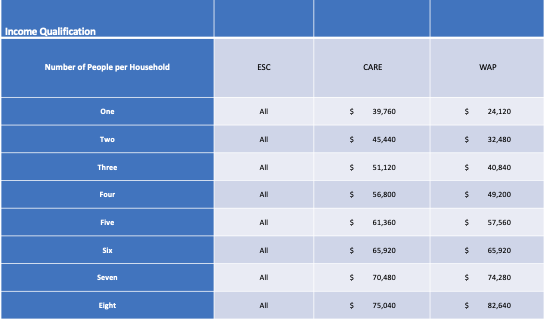

Income qualifications per GV-HEAT program as gross annual household income “With the cold weather approaching, this is the time to find out how to make your home more energy efficient.” said Gesa Michel, GV-HEAT Coordinator with the GVRHA. “Take advantage of enrollment for all of these programs today!” For more information and to get signed up please visit GVRHA’s website or reach out to Gesa Michel, at [email protected] or 970-234-5613. Written by Gesa Michel with GV-HEAT

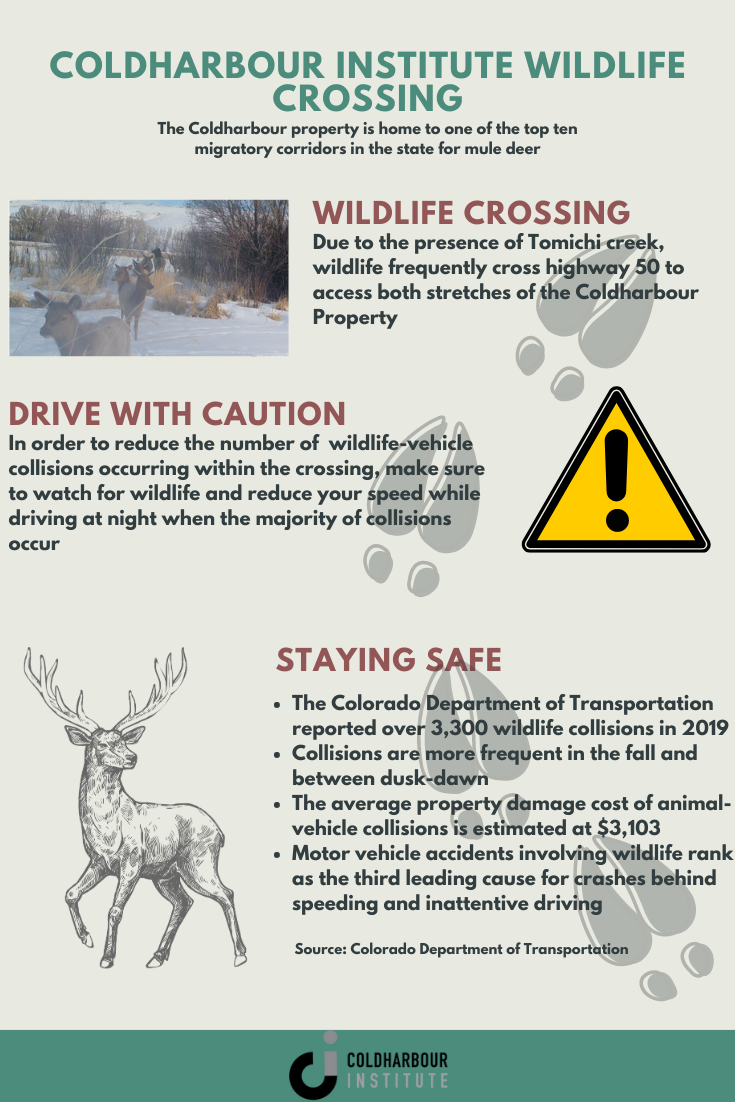

Home Energy Advancement Team Making energy efficiency and home repairs accessible for every household in Gunnison County In 2019, Ashley Merkel, a Masters of Environmental Management alumni from Western Colorado University conducted a project to create a Wildlife Management Plan for the Coldharbour Ranch. In doing so, she discovered and defined one of the top ten wildlife corridors for mule deer in the state of Colorado. Coldharbour Ranch happens to lie within a migration route that ungulates travel along in order to reach summer and winter ranges in the Gunnison Basin. This migration route crosses Highway 50, along a north-south axis. Out of 334 total acres, 243 of those acres constituting Coldharbour are under a conservation easement. No development or livestock ranching is permitted on the land protected by the easement. This allows for wildlife to roam uninhibited on the land without competition from cattle and the presence of Tomichi Creek on the Coldharbour property provides the much needed resource of water. The conservation easement has most likely created a safe haven for wildlife especially in an area that has become developed and most open ranges are being used to ranch cattle. The migration corridor is just now being studied and looked at but has probably been used by wildlife long before Gunnison was founded and settled. The only difference is that now the corridor crosses a major highway. Over the years, wildlife-vehicle collisions have increased along this stretch of highway (Pankratz 2016, Webb 2019). These collisions happen more often in the winter when snow banks from plowing the roads create obstacles and slow down ungulates from crossing the highway (Webb 2019). There is a lack of signage where this corridor is located informing drivers to be extra alert for potential mule deer crossings. Wildlife-vehicle collisions are concerns along any roadway and safe wildlife corridors are an effective solution to reduce the number of collisions. Wildlife corridors such as overpasses and underpasses have been used for decades in European countries. The use of wildlife corridors is becoming increasingly prevalent in southern US states such as Wyoming, Nevada and Oregon. Public support of wildlife corridors in New Mexico and Colorado is 85% according to a recent poll from the National Wildlife Federation. In August of 2019, Colorado Governor Jared Polis signed an executive order directing state agencies to identify and protect wildlife corridors. With recorded mule deer crossing Highway 50 and connected roadside casualties there is a recognized need from Coldharbour to protect this corridor. The executive order from Governor Polis includes direction to the Colorado Department of Transportation to enable safe wildlife passage and efforts to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions. There are several proven methods that have been utilized to reduce deer-vehicle collisions and raise public awareness of key migratory routes. Introducing signage in advance of crossings has been shown to reduce the number of collisions. This is a simple and effective first step to reducing vehicle-wildlife collisions along Highway 50 before a larger project such as a wildlife overpass can be put into place. It is the goal of Coldharbour Institute to support this wildlife corridor, and work with important community partners such as CDOT and Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) to utilize best practices to establish a more safe wildlife corridor, both for the crossing animals and the people of the Gunnison Valley. Pankratz, H. (2016, May 08). Study: More cars hitting wildlife on highways in Colorado, nationwide. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://www.denverpost.com/2008/01/31/study-more-cars-hitting-wildlife-on-highways-in-colorado-nationwide/ Webb, D. (2019, March 21). As deer become more active, drivers urged to be vigilant. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://www.gjsentinel.com/news/western_colorado/as-deer-become-more-active-drivers-urged-to-be-vigilant/article_7e798868-4b95-11e9-8850-20677ce06c14.html Written by Anna Markey, Kathryn Bickley, and Lily Richards. Students in the Master of Environmental Management at Western Colorado University.

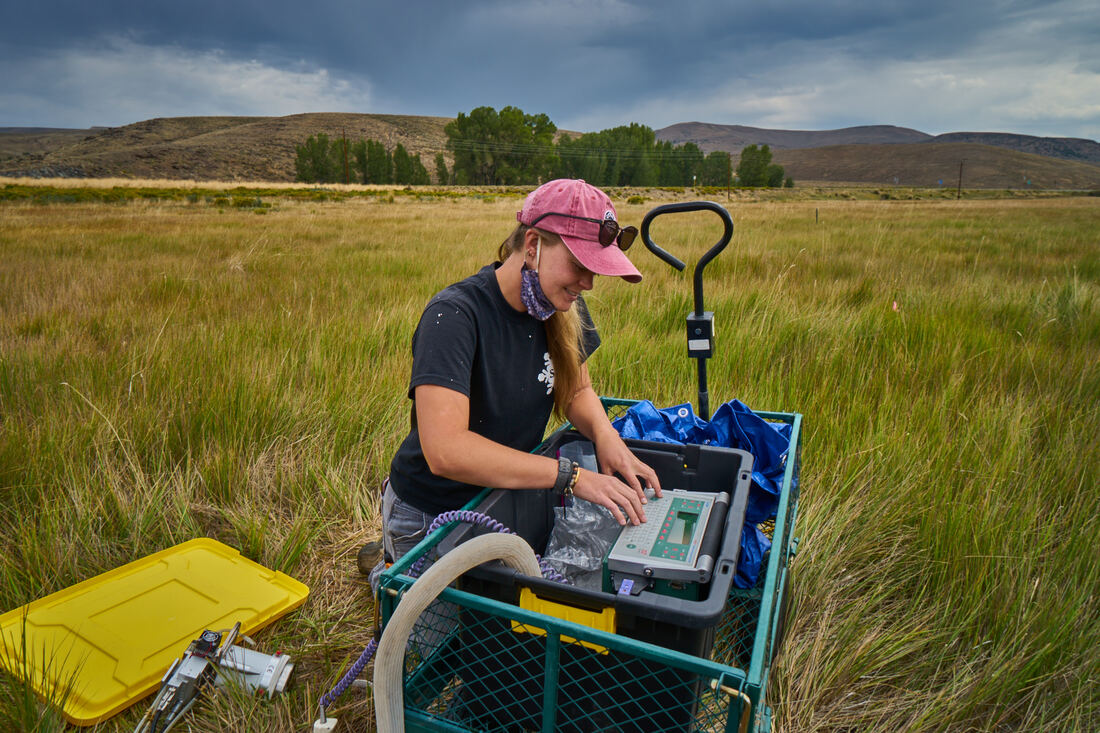

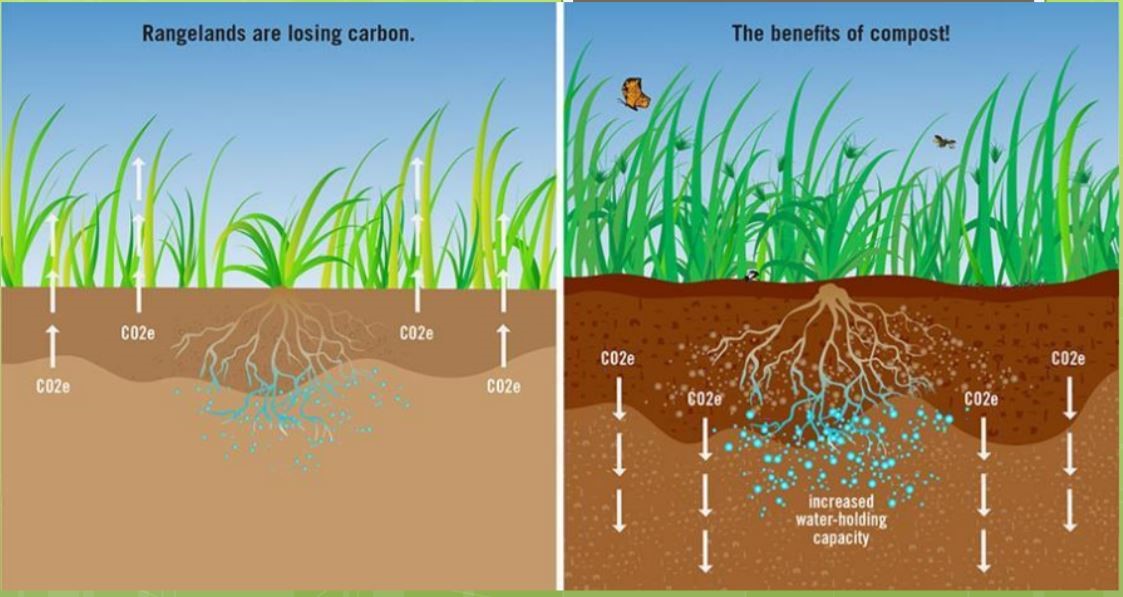

For my thesis research, I am interested in the carbon sequestration potential of rangeland soils. Rangelands present a valuable opportunity to sequester carbon as they are continually managed grasslands with high productivity. At Coldharbour, and two other rangeland sites, compost was added to the soils for the purpose of increasing soil water holding capacity, plant productivity, and carbon sequestration. These compost additions were carried out in June of 2019 by Alexia Cooper, a Western MEM Alumni. My role in this project investigates the impact that compost additions have on soil respiration, that is, the release of CO2 by microbial organisms within the soil microclimate. Using the amount of respiration given off by these microbial organisms, and by testing the amount of soil organic carbon present, I will be able to calculate the mean residence time of carbon within the soil. The major goal of soil carbon sequestration is to increase the length of time that carbon resides within the soil profile. If I am able to find that compost additions indeed increase this residence time of carbon, then implementing compost additions may be an impactful strategy employed by ranchers to improve rangeland soil health while also supporting climate change mitigation. Pictured is a piece of equipment that measures the amount and rate of CO2 released from the soil. I am also collecting soil moisture and soil temperature weekly and will be identifying the soil microbial communities within each plot in the summer and winter seasons to further understand the shifts that occur on an annual basis. I hope with the collaboration of Coldharbour Institute and Western Colorado University that my research results may go on to support impactful management strategies in rangeland soil health for the benefit of Gunnison ranchers, community members and overall environmental health. Written by Alexandra VanTill, Student in the Master of Science in Ecology and Conservation program at Western Colorado University

Introduction into Science December of 2019, after hours of plant biomass separation, weighing, and data input and analysis, my mentor Alexia and I looked at our first preliminary graph. In this moment, I became hooked on soil science. All the exciting field work and tedious lab work paid off with amazing data showing a trend toward multiple compost benefits. My name is Shaun McGrath and I am an undergraduate Environment and Sustainability student at Western Colorado University (WCU) transitioning into the Master in Environmental Management (MEM) graduate program. In September of 2019, I was lucky enough to be offered a paid internship with MEM student, Alexia Cooper, working on her research addressing rangeland resilience through soil health and compost amendments. Throughout my year helping Alexia, I discovered my passion for soil science and the benefits of healthy soils. My experience working with Alexia was a rare one for an undergraduate. Alexia Cooper was awarded the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) grant, which fully funded her project including a stipend for both herself and me. Even though no scientific research can be characterized as ‘easy’, having funds and resources made the process easier. Initiating My Own Project With strong momentum at the end of Alexia Cooper’s master project, I was excited to take a soil ecology summer course with Dr. Jennie DeMarco at WCU and initiate my own soil health research. With this excitement, I was ambitious with my goals. Carbon sequestration, the storage of atmospheric carbon dioxide in the soil, peaked my interest and made me curious if the compost amendment increased the soil’s ability to mitigate climate change by increasing this sequestration. One indicator of an increase in soil carbon is the stability of aggregates within the soil (Djori, et al. 2019). Soil aggregates are clumped pieces of primary soil particles, soil carbon, and organic matter (Word Press, 2019). These aggregates contribute to soil aeration and water and nutrient cycling. My objectives at the beginning of my project were…

Challenges Faced: Student Scientists and Land Managers Early on I discovered many research challenges that I did not have to face while interning for a fully-funded project. Mainly, the time constraint of a summer course proved to make quality scientific research difficult. I would not be able to take accurate data, analyze, and produce a comprehensive write-up within the four weeks I was allotted for this project. Financial and lab resources were the other challenge I faced when attempting to reach my original project objectives. WCU has a young soils lab, so resources and equipment are often minimal. The COVID-19 pandemic also made access to the soils lab difficult. These challenges are also common for land-managers who do not have the financial ability or access to a lab to perform research. Ranchers are not necessarily resistant to change, but do not have the resources to address their needs or questions. These limitations must be addressed to increase rancher and student participation in land health. Science and Land Management with Limited Resources With so many obstacles preventing my ability to answer my short-term research objective, I altered my project to address future students and ranchers who were in the same position. Research is often halted by a lack of resources, but low-cost and low-time commitment options are available to those students and land managers motivated to follow their curiosity without the assistance of a grant. My new project objectives became…

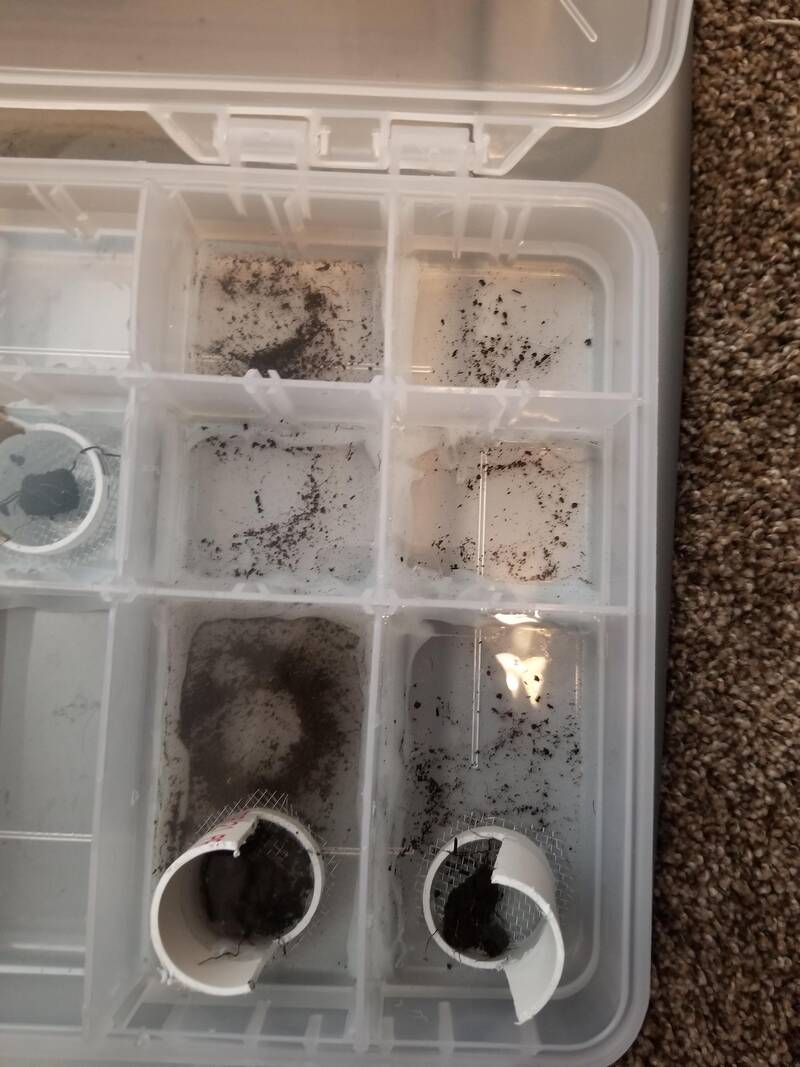

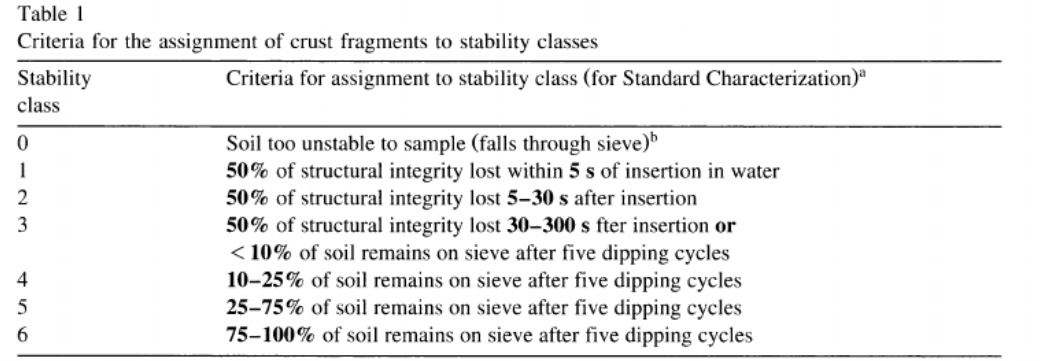

To address my lack of resources and time, I created my own soil aggregate stability kit designed to perform quick, in-field, qualitative research measuring the class stability of soil introduced by Herrick, et al. (2001). This kit took me just two hours to create. Class 0 soil is the least stable where class 6 is the most stable. This article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0341-8162(00)00173-9. The directions for creating the kit can be found at https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_050956.pdf on page 38 and the methods on page 20. I adapted the following instructions and method from Herrick, et al. (2001). Required materials:

Instructions:

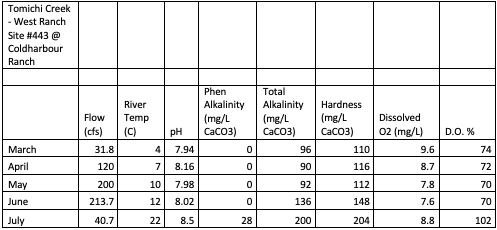

I followed the methods provided by the USDA to test a total of six soil samples. Three from the control sites with no compost application and three from the treatment sites with two inches of compost top-dressing. I was able to test these samples in 45 minutes and could easily upscale to more samples, as there is a total of eighteen slots in the soil kit. This method proved to be feasible, affordable, and easily replicable for student soil scientists and land-managers seeking to understand the stability of their soil. Outcomes My qualitative data revealed that the treatment soils tended to have more stable aggregates as most of the soil remained in the sieve after the slake test. The control samples tended to have slightly less stable aggregates as about 25% of the soil samples fell through the sieve during the test. I characterized the treatment soil as stability class 6 and control as stability class 5 according to the table in figure 1. This result was expected as an input of soil organic matter and an increase in plant biomass production after compost amendments tend to increase soil carbon and therefore increases the stability of soil aggregates. This data can be confirmed using quantitative lab methods in a future project. Through offering my experience of a short, self-supplied research project, I hope to encourage current and future students and ranchers to initiate projects to address their questions without the intimidation of limited resources. Even if one does not desire to learn about soil aggregate stability, there are likely many more papers similar to the one I found offering low-cost and low-commitment alternatives to lab equipment. Every curious mind deserves for their questions to be answered without financial ability interrupting their path. Written By: Shaun McGrath Western Colorado University School of Environment and Sustainability 17 August 2020 Special thanks to Dr. Jennie DeMarco for guiding me through soil ecology and to MJ Pickett for facilitating a beautiful location for student research at The Coldharbour Institute. References Dorji, T., Field, D.J., Odeh, I.O.A. (2019). Soil aggregate stability and aggregate-associated organic carbon under different land use or land cover types. Soil Use and Management, 36(2). https://doi-org.ezproxy.western.edu/10.1111/sum.12549 Herrick, J.E., Whitford, W.G., Soyza, A.G., Van Zee, J.W., Havstad, K.M., Seybold, C.A., Walton, M. (2001). Field soil aggregate stability kit for soil quality and rangeland health evaluations. CATENA, 44(1), 27-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0341-8162(00)00173-9 USDA. Soil Quality Test Kit Guide, Jul. 2001, https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_050956.pdf. Word Press. "Soils Matter, Get the Scoop!" 15 Jul. 2019. https://soilsmatter.wordpress.com/2019/07/15/what-are-soil-aggregates/. Over the past five months, Jesse and volunteers have been collecting water quality data on Tomichi Creek at Coldharbour ranch. This is located in a beautiful fluvial valley just East of Gunnison where there is a wetland easement on the property to protect local and migrating birds. The information that is collected is input into the River Watch database which can be accessed by the public, volunteers, students, and organizations throughout. It has been a great experience so far and there has been a lot of variability in the different parameters that are tested. Each month it has been exciting to collect, test, and see the results and important to understand what this data represents. Some of the largest variability has been in dissolved oxygen, alkalinity, and hardness. We also measure pH, temperature, and flow of the river. These all interact, and as testing continues and River Watch expands, the opportunity to understand and monitor Colorado’s waters continues to grow. If you are interested in volunteering please reach out to Jesse at [email protected] Written by Jesse Bryan, Clark Fellow and River Watch Educator Jesse's interests lie in aquatic restoration and he currently facilitates the Coldharbour River Watch volunteer program, which establishes monthly water quality data on Tomichi Creek utilizing a citizen science approach. Jesse hopes to pursue postgraduate education after he graduates from WCU to study with a watershed science program.

Coldharbour Institute aims to provide meaningful research that is site specific and focused on addressing the expressed needs of our community. We want the research that is developed by our team to be applicable to our region with results that drive innovation and adaption. Ranchers and academia have a fraught history that has hindered efforts for collaboration. We wish to change that, evolve it to create the change that is needed to address the issues that face our community. At Coldharbour Institute, we intentionally approach ranchers in our community with a humbleness that promotes collaboration and a co-production in knowledge to move forward issues. In the Gunnison Valley our land managers face a variety of issues from invasive weeds, wildlife conflicts, and a changing climate e.g. a longer drought period. We want to build an adaptive and dynamic relationship between Western Colorado University and that of the producers in our valley. Coldharbour Institute provides the land for us to test our research ideas informed from our community needs assessments. For many of the fellow’s projects, access to land was vital to test our land management approaches. The Coldharbour Ranch boasts a diversity of ecosystems to experiment upon, from riparian to sagebrush steppe. There is a symbiotic relationship formed by our passionate graduate students and their community-based work which provides Coldharbour with innovative research that supports our goal to demonstrate holistic land management practices to prompt adoption by our community. A drone shot taken early June by Alexia Cooper, shows the flooded Tomichi Creek and its tributaries. An Example of this Approach: Rangeland Resilience through Soil Health In Gunnison, we have a long and rich ranching history that goes back more than a century. The continuation of this ranching culture relies upon the conservation and regeneration of the perennial rangelands that ranchers rely upon. In 2018, our valley experienced a prolonged drought period, and in response, ranchers had to shut off their flood irrigation two week early to conserve water. Here in our cold high elevation climate, we have a very short growing season of just 62 frost free days. Due to the shortness of our growing season, a two week decrease in water drastically affected the yields of ranchers lands. After the economic results were felt by ranchers, they were apt to find a solution to make themselves and their lands more resilient to the effect of drought. One way to do this was to improve the health of their soil, specifically the water holding capacity of their soil. A promising approaching to achieve this was to amend their soils with compost. As a graduate student at Western Colorado University, I had just listened to a lecture by a premier soil scientist in California, Rebecca Ryals, who had conducted a research project to find out how to regenerate rangelands from the soil up. Her approach was to apply a half an inch of food waste compost to rangelands. In their first year, they saw a doubling forage production, an increase in the water holding capacity of the soil, and a 70% increase in net ecosystem storage of carbon. Her project demonstrated that it was possible to improve the health of the ecosystem; while mitigating climate change by fostering increased soil carbon sequestration. I was deeply impressed on how this project interwove community needs, climate action, and impactful policy into a monumental force for change. This inspired me to focus my master's project on a replicate study here in Gunnison. For my project I applied two inches of Class A biosolid compost to four ranches. One of the four sites was located on Coldharbour Ranch. Coldharbour Institute is my community sponsor, and they guided my research objectives to meet the needs of my community. The goals of my project was to discover if the application of compost would demonstrate similar positive effects like seen in the Californian study: improved water holding capacity, increased forage production, and increased storage of carbon from the atmosphere. Throughout the summer I monitored soil moisture, plant biomass, species diversity, soil temperature, and in the fall, I collected soils to run soil health analyses. Although it is still early in my data analysis, I observed an increase in grass production and an increase in soil moisture throughout the summer in my treatment plots. My project creates a connection between Western Colorado University and the ranching community in Gunnison, setting it up for future collaboration and growth. This revamped connection was made possible through the network and high community standing that Coldharbour Institute has built since its inception. Ranching culture promotes individualism and self-reliance and historically, ranching communities dislike academic involvement within their land management. This is due to the typical relationship that is formed: researchers go into the ranching community with a sense of superiority that often belittles and dismisses the traditional knowledge ranchers have gained through trial and error. There is little to no room for collaboration when defining the purpose and research goals of the project. Researchers conduct their projects and leave without debriefing the community about the results of their research. This is an issue that is perpetuated by a lack of good science communication. For researchers, it takes an additional awareness and intention to begin the discussion early with ranchers and managers, this prompts collaboration. And then, the researchers should conclude it by sharing how their findings can inform, for example, land management, city planning, or conservation practices. Written by Alexia Cooper, Clark FellowAfter graduating from the MEM program this coming May, Alexia will be pursuing her PhD at UC Merced working with Rebecca Ryals, from the Marin County Carbon Project, on soil carbon sequestration project in California.

We are engaged with many forms of research and ecological monitoring at the Coldharbour Institute including camera trapping, water quality testing, transects, wetland delineation, and plant surveys. With Western Colorado classes, past and current Clark Fellows, and other local learners involved with Coldharbour you can imagine we have no shortage of data. As a learning hub engaged in a regenerative network, we have a stewardship responsibility to the data (as we do to our land). Shared file organization with a logical, clear structure and labeling system not only makes it easier for our team to find data, but also enables our partners to access relevant data. Coldharbour Geospatial Data Management With Coldharbour’s many partners and research projects, data management is an iterative process but most recently we’ve tackled our geospatial data in ArcGIS. GIS data can be stored in many different formats. We opted to use a file geodatabase for storing and managing geospatial data as we have complex data storage needs. A File Geodatabase is essentially a folder for ArcGIS that offer structural, performance, and data management advantages. Setting Up a Coldharbour Geodatabase We are fortunate to have access to Western Colorado University’s shared GIS server which allows multiple students to collaborate on our File Geodatabase and for us to have a comprehensive inventory past students’ data.

Thinking about how you will organize your files and data early on can save you from having to reorganize and rename files later or having to track down important information. We’re still implementing data management beyond our geospatial database so stay tuned for future news updates and best practices that we learn along the way! Coldharbour Institute is a learning laboratory for regenerative living practices. Learn how you can support our research and mission today! Written by Chloe Beaupré, Clark FellowChloe is interested in wildlife - particularly, big game ungulates - and geospatial analysis. You can find her making maps of the Coldharbour property or behind a pair of binoculars. |

Ongoing ResearchNotes from the field of Coldharbour Ranch. Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|

Sign up for our newsletter below.

|

|

Coldharbour Institute is a 501(c)3 Non-Profit Organization

P.O. Box 463 Gunnison CO 81230 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed